This post continues our series of articles on Automatic Speech Recognition, the foundational technology that powers Descript’s automatic transcription. The marquee article in this series will test the accuracy rates of today’s biggest ASR vendors — like Google, Amazon, and IBM. Before we publish the results, we wanted to explore the reasons why declaring one ASR provider to rule them all is a bit trickier than it sounds.

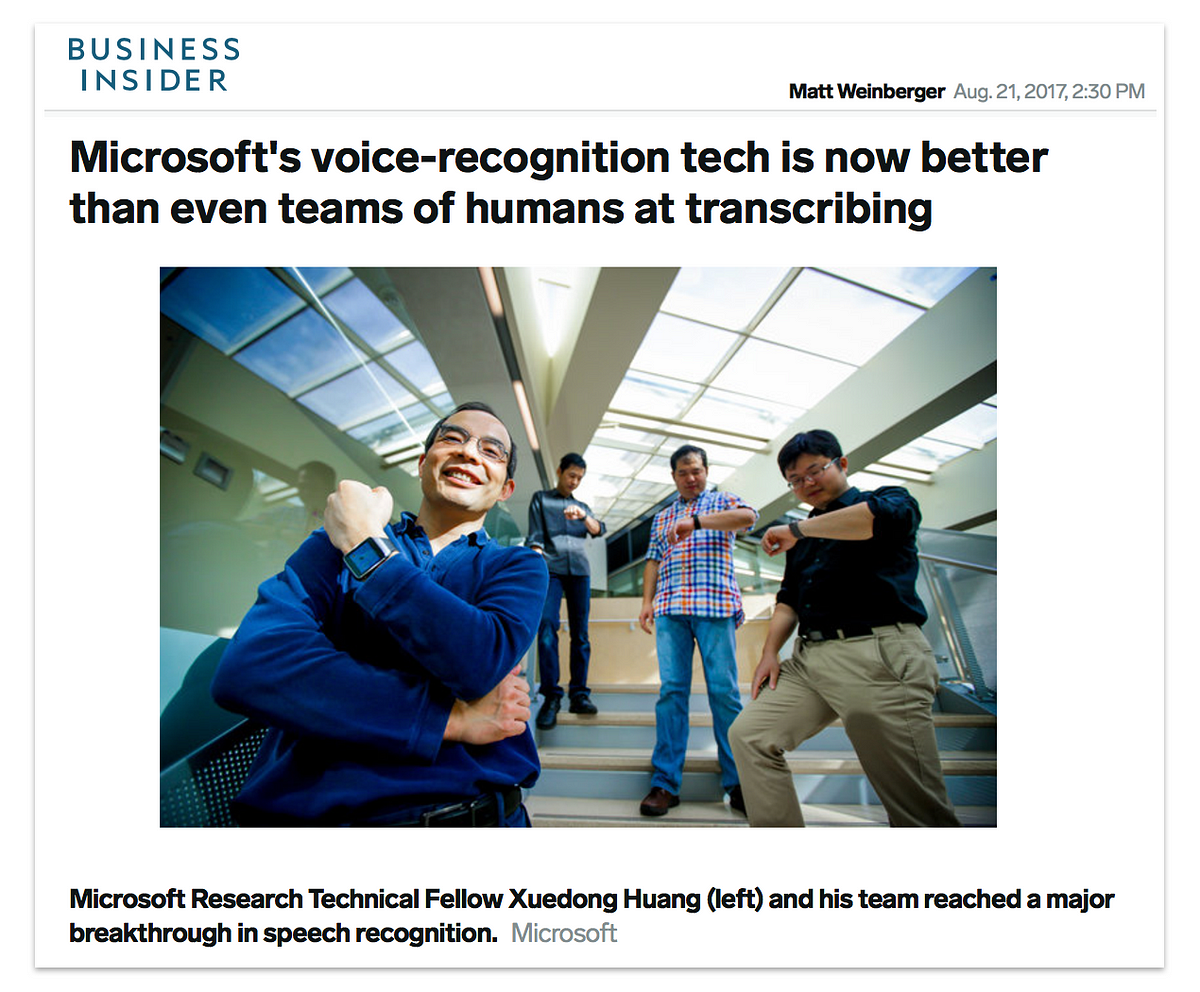

Over the last couple of years you may have seen headlines proclaiming that AI-enhanced computers have reached parity (and even surpassed!) the speech recognition capabilities of humans. It’s a claim that’s both exciting and — given the “creative” interpretations of voice assistants like Siri and Alexa — tough to swallow.

Speech recognition has gotten better, sure. But try using your phone to record a typical, noisy meeting in a boomy conference room—then pass the resulting audio through one of the leading automatic speech recognition engines. You’re liable to wind up with something closer to word salad than meeting minutes.

So what are these researchers on about? To understand why their claims actually have merit — and the associated caveats—we need to explore the industry’s standard accuracy test, Word Error Rate.

How Word Error Rate Works

Measuring transcription accuracy seems like a task that should be reasonably straightforward: you tally how many words the transcription engine gets correct, contrast that with how many it got wrong — and there you go… Right?

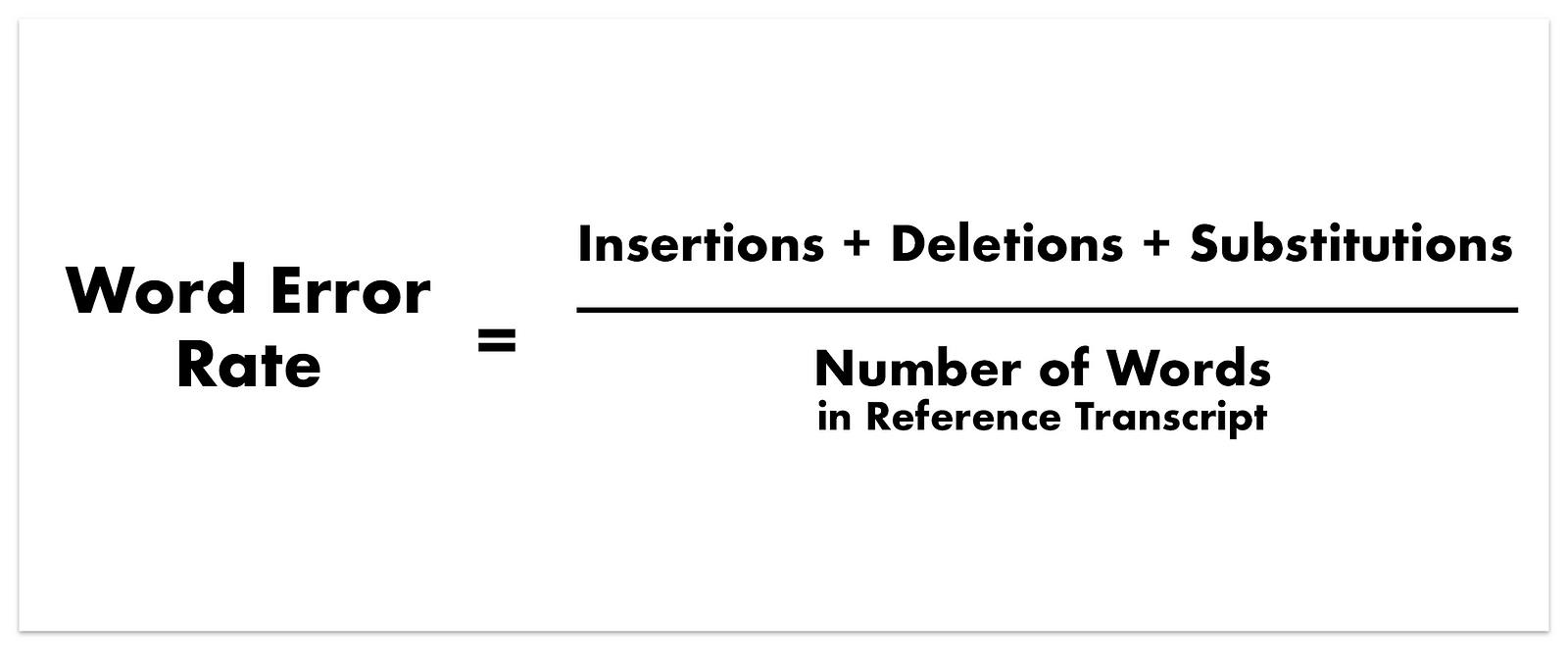

And indeed, that’s essentially how the experts do it. They use fancy math formulas and terms like Word Error Rate (WER) and Levenshtein distance, but conceptually it’s pretty intuitive: words wrong, divided by the number of words that should be there. It’s a linguistic batting average.

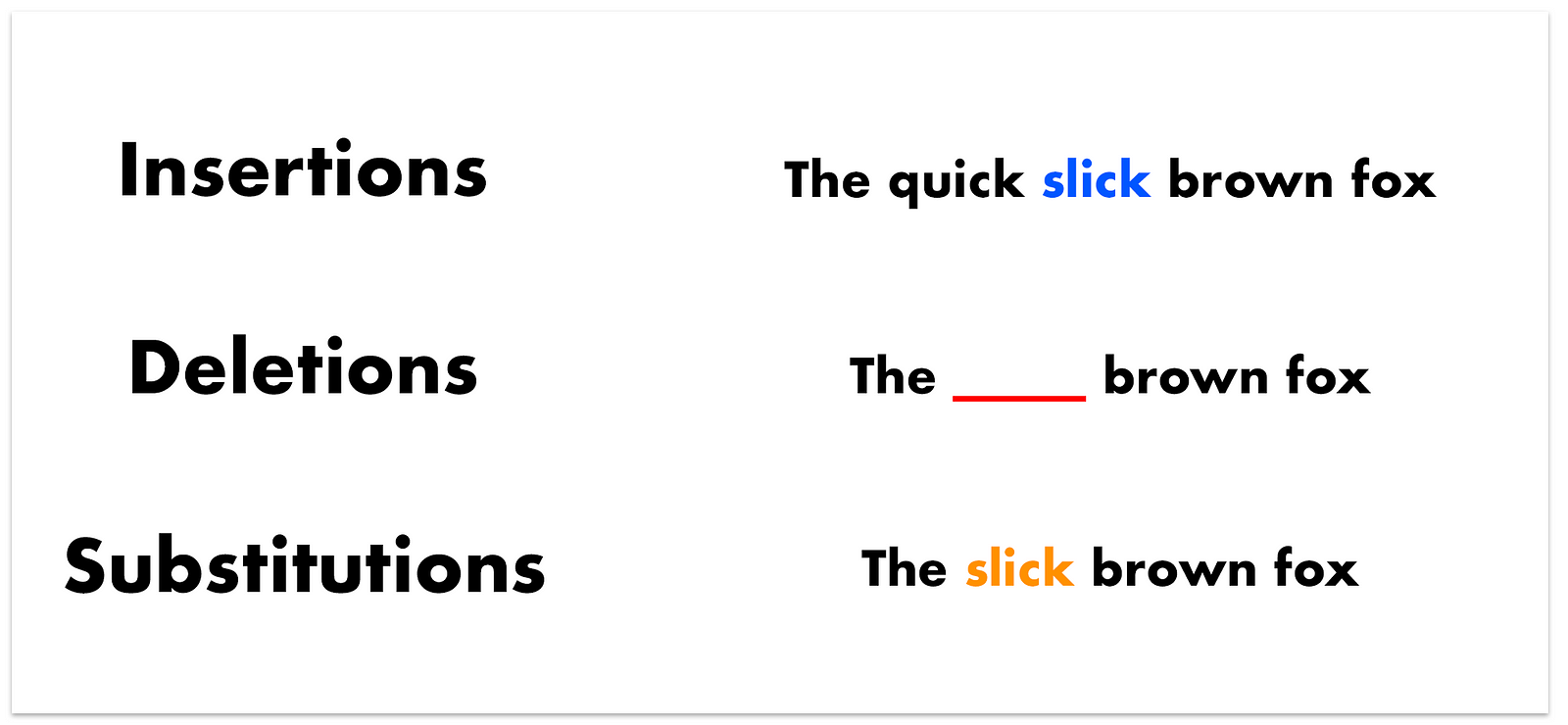

At a high level, WER works like this: add up the number of words that the ASR engine got wrong — namely words that have been incorrectly Inserted, Deleted, or Substituted — and divide that by the number of words that should be in the transcript. The resulting percentage is your Word Error Rate.

Now, in order to discern what the ASR engines are getting right and wrong we need to have an accurate transcript to compare to. These are called reference or ‘ground truth’ transcripts, and they’re hand-transcribed and checked by humans. Each reference transcript is then automatically aligned with its ASR-generated counterpart, so the test can tell which words are supposed to be where. This is important: if the test isn’t using the optimal alignment, it can count what should be a single Substitution error as a pair of Insertion/Deletion errors, inflating the WER.

You may be wondering how WER handles stylistic differences. For example, some ASR engines will transcribe numbers as words, while others use the corresponding digits (1, 3, 5). And if an ASR engine says “going to” but the source transcript says “gonna” — what then? Such cases are addressed via a normalization process that specifies which contractions are valid, that “Street” and “St.” mean the same thing, and so on.

Issues with WER

The fundamental problem with WER is that every word is worth the same number of points. Whether it’s a name or adjective, “a” or “Antarctica” — they all count the same.

Of course, reality tends to disagree: anyone could tell you that not all words in a sentence are equally important — and that some errors matter more than others. But because these factors depend on context and meaning, it’s difficult to develop a test that can be broadly applied without a litany of caveats.

Which is why you’re reading a litany of caveats.

Along with ignoring the importance of words, WER is also a brutally harsh judge: it gives no partial credit. Even if a mis-transcribed word is just one character off, WER treats it the same as a complete, nonsensical whiff.

Now consider the following two sentences:

- It’s a matter of free peach.

- It’s a matter of free.

Using Word Error Rate, these two sentences would receive the same score: it’s just as bad to transcribe “peach” as it is to simply omit the word. To a human, the first sentence is obviously more useful — but WER doesn’t care (granted, if the ASR engine guessed “free lasagna” nobody would be campaigning for partial credit).

Another issue with WER is its total disregard for speaker labels and punctuation. These may or may not be important, depending on your use-case—but it’s obviously a major simplification.

It’s also worth considering what we even mean by “accuracy” in this context. A 100%-verbatim transcript is likely to include many words that are essentially meaningless: “uhms”, “uhs”, false starts, and duplicates — words that can actually interfere with reading comprehension. We can tweak the test to account for some of this, but it’s a good reminder that WER is just a proxy for evaluating how transcripts will be used in the real world.

Better than the Rest

Despite these compromises, Word Error Rate is the most widely-used measure of transcription accuracy by a long shot, and it’s what we use for our testing. While imperfect, its prevalence and endurance in the field attest to its utility all the same.

There’s also a body of evidence that shows that WER correlates with other measures of accuracy that the test itself doesn’t take into account, like Keyword Error Rate — which weights each word depending on its likely importance (and is vastly more complex to calculate). After conducting an experiment comparing the two metrics, researchers concluded “the use of Word Error Rate is sufficient especially for cases where WER remains below 25%.”

Even WER’s critics begrudgingly admit its supremacy. In a research paper asking Does WER Really Predict Performance? — which is generally fairly critical of WER — the authors state the following:

“The purpose of this paper is not to postulate a better alternative to WER for evaluating transcript quality; we stipulate that no better alternative likely exists if the task at hand is taken to be speech transcription for its own sake.”

WE’Re Winning!

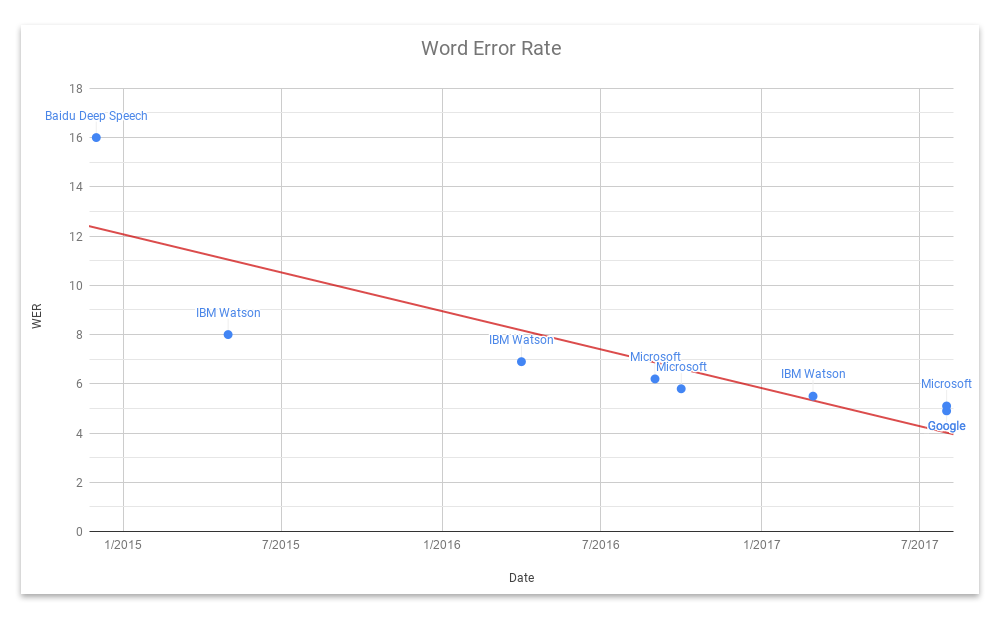

In recent years, researchers from Baidu, IBM, Microsoft, and Google (among others) have been sprinting toward wringing ever-lower Word Error Rates from their speech recognition engines — with remarkable results.

Spurred by advances involving neural networks and deep learning, along with massive datasets compiled by these tech giants, WERs have improved enough to generate headlines about meeting and surpassing human efficiency, based on findings that professional human transcriptionists have a WER of around 5.1–5.9% (people mishear things a lot!).

In contrast, Microsoft researchers report their ASR engine has a WER of 5.1%; IBM Watson’s 5.5%. And Google claims an error rate of just 4.9%.

The catch is that most of these tests were conducted using the same set of audio recordings: namely a corpus called Switchboard, which consists of a large number of recorded phone conversations spanning a broad array of topics. Switchboard has been used in the field for many years and is nearly ubiquitous in the current literature—so it’s a reasonable choice. By testing against the same audio corpus, researchers can make apples-to-apples comparisons between themselves and competitors. (Google is the exception; it uses its own, internal test corpus, which is opaque to outsiders).

But this homogeneity leads to a sort of tunnel vision: those claims of surpassing human transcriptionists are based on a very specific kind of audio. If the footage you’re working with doesn’t involve phone calls — then which system is best? Audio is not one-size-fits-all: depending on whether footage has been recorded via a phone or professional mic, from two inches or twenty feet away, with or without accents, featuring two people or twelve — there are a lot of variables, and they can have a substantial impact on transcription accuracy.

That’s one reason Descript decided to run its own tests: we deal with so many different kinds of audio, it makes sense to test with a broader sample, and to get a sense for whether different ASR providers excel at different things.