Introduction

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 is the foundation of a complex body of regulations, intended to promote development of a national health care infrastructure. A key subset of those regulations, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act), was signed into law on February 17, 2009 (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2009). In addition to strengthening enforcement of privacy and security provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, the HITECH Act established incentives to providers and hospitals for the adoption of electronic health record (EHR) technology.

Eligibility for incentives requires the organization verify the EHR is utilized in a meaningful manner. Meaningful use is demonstrated by “the use of certified EHR technology in a meaningful manner…that provides for the electronic exchange of health information…to improve the quality of care” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012, para. 1). Selection and implementation of an EHR are not a guarantee of success. Full adoption evidenced by meaningful use of the technology by end-users “is crucial to achieving the intended effects of the systems” (Granlien & Hertzum, 2012, p. 216).

Problem Statement

The project setting was an integrated health care delivery system in California comprising six hospitals, multiple ambulatory clinics, a skilled nursing facility, and an array of subacute, transitional care, rehabilitation, and home health and hospice programs. In response to widespread unmitigated problems with its existing EHR platform, the organization’s executives undertook urgent plans to implement a replacement EHR, Epic. A compressed timeline for implementation of the EHR posed significant financial challenges, and led the executive team to aggressively pursue expense mitigation strategies for labor costs associated with the project.

Super-user Support as Driver of End-user Adoption

A review of the literature, conducted to provide context for the project plan, revealed several studies of factors that influence end-user adoption. A study of EHR implementations in nine hospitals in the United States identified adequacy of training as a key success factor (Silow-Carroll, Edwards, & Rodin, 2012). Other studies re ported product ease of use and adequate hands-on support by peer experts were important drivers of end-user acceptance (Gagnon et al., 2012; Granlien & Hertzum, 2012). One study of clinicians during and after EHR im plementation in one hospital concluded positive super-user at ti tudes enhanced end-users’ percep tions of EHR ease of use and general usefulness (Halbesleben, Wakefield, Ward, Brokel, & Crandall, 2009). Superusers (SUs) “are clinicians who are provided with extensive training on a clinical information system (CIS) in order to assist the end user” (Simmons, 2013, p. 53). In addition to facilitating end-user skills development, SUs may also impact other employees’ attitudes toward the new technology (Simmons, 2013).

Extensive evidence supports the SU model for EHR implementation (Bornstein, 2012; Laney, 2013; Simmons, 2013). During such projects, direct-care staff serving as SUs are relieved of their normal duties to focus exclusively on providing at-the-elbow support for end-users. This temporary reassignment requires alternative coverage to backfill the clinical shifts that would normally be worked by the super-users, who are often the most experienced and knowledgeable members of the direct-care teams. Simon and co-authors (2013) reported backfilling super-user shifts with premium labor resources not only increased hard costs such as labor expense, but produced soft costs in the form of employee and physician dissatisfaction with the disruption of usual clinical work teams. This finding was consistent with the health system’s experience during previous technology implementations, and executive leaders were eager to explore alternative approaches to covering super-user shifts during implementation of Epic.

Outcomes

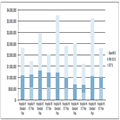

The innovative super-user workforce model reduced labor costs associated with super-user staffing by 31.8%, as compared to the standard super-user model proposed by the vendor. This expense reduction was achieved in spite of total super-user hours having been increased by 35% over the standard SU model. Figure 1 depicts the comparative expense by hospital, and reveals the most significant element of super-user expense for each facility was contract labor to backfill the clinical shifts vacated by experienced RNs serving as SUs.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Projected Cost for Standard Super-User Model with Actual Cost of Using EITs as Half the Super-User Workforce

NOTES: SU = super-user; EIT = Epic Implementation Technician

Although not as easily measured as financial outcomes, subtle changes in the organization’s culture and workforce were also observed. Prior to the project, some nurse leaders and staff exhibited a reluctance to hire large numbers of newly licensed nurses, citing the challenges of training and supporting those inexperienced clinicians. After having observed the EITs’ performance as super-users, many of those same nurse leaders and staff were eager to recruit the new nurses to stay on as RN residents. In turn, the EITs hired as RN residents infused increased confidence and competence as users of technology into the clinical staff with whom they worked. Within 12 months of being hired, many of the former EITs were active participants in various nursing councils and informatics teams in their facilities.

Conclusion

The role of super-user is a critical element of an effective EHR implementation project. In spite of the considerable evidence supporting the effectiveness of experienced RNs as EHR nursing super-users, the practice increases project cost and the risk of disrupting continuity of care as a result of reliance on contract labor to fill shifts vacated by the super-users. Tapping into the local workforce of newly graduated RNs serves as a cost-effective means to reduce costs and minimize staffing disruption during the implementation of a new EHR.